What is Reality? How can we discover the ultimate

physical/mathematical laws which govern its evolution in time – or govern its

state across space-time?

February 2018: Like many people who have taken serious courses in

quantum field theory (QFT), I have tried to think strategically about the basic

question: “HOW could we someday come to learn the true ‘law of everything’?”

But when the NSF Engineering Directorate asked me to take charge of advanced

research in practical quantum electrodynamics (QED) for electronics and

photonics, I was amazed to learn just how much difference exists between

different theories of QED used in real-world work, let alone other branches of

physics further from experiment. See https://arxiv.org/abs/0709.3310

for where we started in that effort.

This

is an extremely tricky area. I am very grateful to the leading physicists,

especially in quantum optics, who have helped me sort out the real challenges

here, and develop a practical, empirical path forward. Because this web page

was destroyed and hacked a few days ago, let me point directly to the two most

up-to-date papers giving my best new understanding of what needs to be done

next, both to put on us a more solid path to understanding how the universe

works and to deploying a whole new level of quantum information technology far

beyond what the US government is funding as yet: https://arxiv.org/abs/1309.6168 and https://arxiv.org/abs/1309.6168.

2016: A new and more complete explanation may be found in Werbos, Paul J., and Ludmilla Dolmatova. "

What

are the larger philosophical implications if we ourselves are indeed just “macroscopic

Schrodinger cats?” Here is my best effort to integrate these areas, which was

published in Russia:

www.werbos.com/Mind_in_Time.

2015: This past year, I have

filled in many details of my program for “return to reality,” to greater

coherence and return to the scientific method, in physics. Still, there are so

many interrelated issues in basic physics that they take some disentangling,

and it is not trivial to figure out what needs to be fixed first. The

first big fix is that we need to move to time-symmetric physics, which I will

now explain a bit further.

The challenge here is to fix the treatment of time, and make the connection all the way to experiment. There is a whole lot of politics in this. Years ago, when Einstein proposed that “time is just another dimension,” people complained that this violated their “common sense,” the common sense that time is something special, hardwired into their brain, which their brain could not conceive of changing. Einstein replied by saying (roughly) “ your common sense is just a collection of prejudices acquired before the age of sixteen.” Time-symmetric physics, as I will define it here, is simply a matter of doing what special relativity does, and taking special relativity further.

Time-symmetric physics is not about quantum mechanics versus classical mechanics; the key issue for now is between different versions of quantum mechanics which yield different predictions.

Time-symmetric physics is not about overthrowing quantum mechanics, or about building time machines. Those are entertaining subjects, but they are different subjects. Everyone in physics knows that special relativity can be applied to quantum field theories or to classical field theories, or even to classical stochastic models. The same is true of time-symmetric physics. Einstein had interest in many other topics besides special relativity, but physicists usually understand that special relativity is a special subject in its own right, which should not be entangled with cosmological constants or the photoelectric effect or Zionism or the development of the nuclear bomb. In the same way, time-symmetric physics needs to be understood in its own right, especially now that empirical demonstrations may be coming, as important as the Michelson-Morley experiments were in establishing the foundations of physical reality.

I was the first to formulate this modern version of time-symmetric physics (citing various older important but less modern papers)

In the open access paper:

P. Werbos, Bell's Theorem, Many Worlds and

Backwards-Time Physics: Not Just a Matter of Interpretation, International

Journal of Theoretical Physics (IJTP), Volume 47,

Number 11, 2862-2874, DOI: 10.1007/s10773-008-9719-9.

That paper gave the basic principles, including a new way to build physical models at all levels (from basic fields to photonic engineering). But it did not give concrete examples or a decisive test. Those are new this year. They can be done within the realm of electronics and photonics; no big accelerators are needed for this stage.

A key principle is to get rid of what I call barnacles – the ad hoc metaphysical observers in old quantum mechanics, the older mathematical formulation of “causality” in probability theory (we have newer formulations in that field), and even Fermi’s Golden rule as a kind of axiom in predicting spontaneous emission in excited atoms. Whatever the dynamics we assume for the universe – a Schrodinger equation, a Hamiltonian field equation, or whatever – we can derive our predictions from those dynamics alone, and not using the barnacles except as a quick approximation when we don’t have time or reason to study the experiment more carefully.

In 2014, at the conference on Quantum Information and Computation XII, I proposed a new decisive experiment, where the old “collapse of the wave function” barnacle leads to one prediction for the three-photon counting rate, but time-symmetric physics in general leads to a different prediction. In May 2015, at a conference in Princeton, I presented 14 slides giving a nice up-to-date overview of where this stands, and of what time-symmetric physics really is. These issues are not just theoretical or academic issues; they are a crucial first step towards major new opportunities in quantum computing, quantum communication, quantum imaging (such as “ghost imaging”) and energy. Those applications are discussed in my other papers in google scholar and arxiv, but they should not be entangled with the first step, the need to sort out the basic physics here.

And there are other important issues in physics, which I have discussed before... in a web page mainly aimed at a less expert audience...

=================

2011: We don’t yet know how the physical universe works. As of today, there are many unexplained mysteries like dark matter and dark energy which prove that we do not. This page will give my views of what we know and what we don’t know, starting from the basics, as of May 2008.

Before we have any hope

of safely developing radical new technologies like warp drive or third

generation nuclear power or second-generation quantum computing, we would have

to develop a better understanding of how the universe works. As with energy

policy and space policy, we can expect to get nowhere unless we learn how to

apply rational strategic thinking to the long-term goal. Again, the strategic

goal here is to understand reality.

=============

More and more, in basic physics, there have been two levels of theory. There is one level of theory – like Einstein’s theory of special relativity, like the Euler-Lagrange version of classical field theory, and like various general versions of quantum field theory – which provides a kind of general framework for how the universe might work. There is another level of theory, like the modern Maxwell’s Laws for electricity and magnetism, which can be fit into one of these general frameworks. To make real predictions, we need to combine a general framework, plus something more concrete and specific like Maxwell’s Laws.

The General Framework

Many people believe that it doesn’t matter which form of quantum theory we use as our general framework. I disagree. There is very strong empirical evidence which already rules out most of what they teach in theory classes today. For details see:

2008: P. Werbos, Bell's Theorem, Many Worlds and

Backwards-Time Physics: Not Just a Matter of Interpretation, International

Journal of Theoretical Physics (IJTP), Volume 47,

Number 11, 2862-2874, DOI: 10.1007/s10773-008-9719-9.

May 2011: A student recently asked: “Your IJTP paper explains how empirical data strongly refutes the usual version of quantum theory they taught us in graduate school. But it doesn’t say clearly which alternative theory you believe in. Which is it?”

Click here to see my answer to him. Click here to see some earlier discussions and

further material leading up to that paper, and some discussion of other

versions of quantum field theory.

The Specific Fields

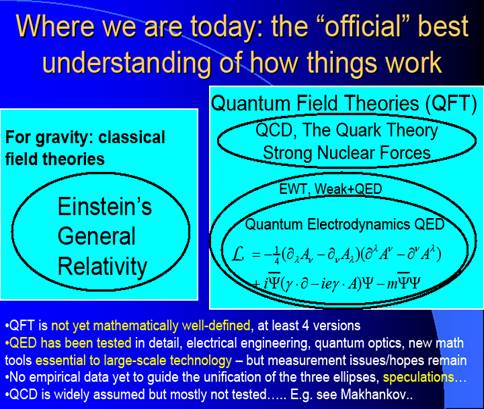

The

slide on the left depicts today’s best “official” understanding of how the

physical universe works. There are three kinds of forces at work in the

universe – gravity, nuclear forces and electricity/magnetism. Physics would

like to develop a nice, clean unified

theory to explain how all types of forces work together. This is certainly an

important long-term goal, but in my view we are not yet ready to jump directly

to that goal. First we need a better understanding, better grounded in

experiment, of the three main pieces – gravity, strong nuclear forces and QED.

All three pieces demand a major cleanup. Until that cleanup happens, our

efforts at unification are basically just a guessing game, an exercise in speculation.

(But don’t worry, I will get around to some speculation on how to unify things,

as I get deeper into the three pieces.)

The

slide on the left depicts today’s best “official” understanding of how the

physical universe works. There are three kinds of forces at work in the

universe – gravity, nuclear forces and electricity/magnetism. Physics would

like to develop a nice, clean unified

theory to explain how all types of forces work together. This is certainly an

important long-term goal, but in my view we are not yet ready to jump directly

to that goal. First we need a better understanding, better grounded in

experiment, of the three main pieces – gravity, strong nuclear forces and QED.

All three pieces demand a major cleanup. Until that cleanup happens, our

efforts at unification are basically just a guessing game, an exercise in speculation.

(But don’t worry, I will get around to some speculation on how to unify things,

as I get deeper into the three pieces.)

But first, for the novice, I need to explain a few things about the slide. The left side is about gravity, which I will soon say more about. The right side is about electricity-magnetism and nuclear forces. Physicists today explain how these forces work by using a unified model called “the standard model of physics.” The “standard model” is a kind of quantum theory made up of two pieces:

(1) “QCD,” which is used to explain the strong nuclear forces; and (2) “EWT”, electroweak theory, which is an extension of QED to account for weak nuclear forces. Quantum electrodynamics, QED, is today’s modern theory of electricity, magnetism and charged particles. Roughly speaking – we have a huge amount of experiments and technology to back up our understanding of gravity (general relativity) and to back up QED; beyond that, we enter the realm of mystery and debate.

In all three areas, a rational strategy basically follows the true scientific method, which goes back to the Reverends Occam and Bayes, to Francis Bacon, to Emmanuel Kant, and to the more modern understanding of intelligent learning systems. According to that method, we try to be open-minded about the widest possible set of possible theories about how the universe works. We rely on experience, on empirical data and active experimentation, to try to probe, test and continually improve our understanding of the universe – and also improve our understanding of just how ignorant we are. We develop theory in order to better interrogate nature and generalize our understanding.

Maybe you think that’s all just motherhood and apple pie.. but there a lot of people who talk about motherhood without really supporting it. Modern science faces more and more problems with people who pay lip service to the scientific method, and “pray to it on Sundays,” but deviate a lot from it in their research. For example, many people in superstring theory have been inspired by the vision which inspired the Catholic Church in medieval times. In those days, the best, most erudite, most polished and socially respectable deep thinkers became entranced by the modern, enlightened ideas of Aristotle. Aristotle had a vision of deducing the one and only possible theory of the universe by enlightened pure reason and logic alone, and then disseminating and enforcing it through a social hierarchy down from the top. So now, instead of epicycles we have superstrings. And who needs alternative theories? I actually remember an NSF review panel where a leading scientist argued that we not fund a certain experimental project because “It is too risky. It risks upsetting the existing theory we have worked so hard to develop.” That was not a superstring guy, as it happens; there are certain difficulties in culture and strategy which have weakened a lot more than just the superstring world.

But now let me get into specifics, the three pieces of physics which require more work.

First, let me start with gravity, which is the easiest. It is the easiest, because today’s work on gravity is the work which is already in best shape. Even with gravity, we do have right-wing crazies, who would want to defend Einstein’s theory of gravity – general relativity – as if it were some kind of Holy Writ. We do have some left-wing crazies, who claim to be able to sell you an antigravity UFO tomorrow. (Some may sheepishly grin, “Hey, it’s not crazy to make a little money here and there. After all, we didn’t say we would deliver it tomorrow. Cash first, delivery a little later.” Let’s not get further into the details…) But between those extremes, we have a solid foundation in play today. To begin with, general relativity itself is a very well-defined theory, and very simple in its essence. It does a good job of predicting and fitting all or almost all of the experiments anyone has ever done with gravity. Even better, we also have an excellent group of serious aggressive scientists in the middle, who are seriously probing rational, clear alternatives to general relativity, such as “torsion gravity,” and solid scientific experiments which rationally try to probe aspects of general relativity where there is the best hope of learning something new. I have not studied this piece of physics as much as the others, but I have seen some excellent papers by Hehl, and an excellent experiment by Yanhua Shih, which provide some examples. If I were a graduate student interest in contributing to this field, I would go to google (scholar) and to arXiv.org, and search on themes like “torsion gravity,” “gravity waves” and “Hehl,” and follow that trail. New understanding of gravity is an important area for government support, worthy of the efforts of the most brilliant new students, and an important area of hope for “warp drive.”

But… it’s not my own area of greatest interest. Why? Because some of us have a duty to try to focus on the greatest problems or obstacles, the biggest messes which need cleaning up, the greatest opportunities which others are not yet doing justice to. Those involve the other two pieces – QED, and nuclear stuff.

Let me again start with the cleanest piece, QED.

First – some review for the novice. QED was the world’s

first “quantum field theory (QFT).” The original theory of quantum mechanics,

developed by famous folks like Planck, Einstein, Heisenberg, De Broglie and

Schrodinger, was not powerful enough to really come to grips with the realities

of electrical and magnetic forces. In a way, it was like a cartoon picture of

what a theory of physics might look like. (Some of my friends in engineering

might say, “It was all just philosophy, like the first adaptive dynamic programming systems you discovered

in the 1970’s.” It wasn’t complete,

but it was a lot more than just philosophy. After all,

QED is also the foundation of the modern electronics industries – electronics, photonics, electro-optics, communications by wireless or optics, computer chips, quantum information technology, and more. Modern research in “electronic” engineering includes all of those fields, and uses QED directly in modeling and design of the next generation technologies. (Half my core job at NSF today is to support that kind of modeling work.) This is an area which is truly driven by practical experimentation. Theoretical physicists will normally tell you that QED has been proven to work, with twelve decimal points of precision.

So how could anything still need cleaning up?

To begin with, there has developed a huge gap between the

understanding we get from experiments and what they teach in school, even to

theoretical physicists, many of whom still believe the old stuff. My recent paper in the International Journal

for Theoretical Physics explains some of that, and what we need to do to

clean it up. Note the preliminary discussion of experiments in the appendix. In

my view, the kind of empirical work discussed in that paper is – like gravity –

one of the most important threads of real hope and real potential progress in

physics today. Unfortunately, because it is a new effort, and because there are

many levels of confidentiality I am obliged to respect, I cannot say more just

yet. But here is one hint – I do believe it opens up the possibility of a

second generation of quantum computing, far more powerful than the first. I

would claim that David Deutsch of

As of today, I also appreciate the need for another stream of work to clean up QED. In the recent paper, I argue that the best practical foundation for physics today is a many-worlds version of quantum field theory. According to that version of quantum field theory, all of the dynamics of the universe are expressed in a single equation:

![]() ,

,

where ![]() is the “wave function

of the universe,” the dot represents the change with respect to time, “i” is sqrt(-1), and H is a

strange object called “the normal form Hamiltonian.” (My apologies to the

novice.) Different choices for H correspond to different theories of physics.

For example, the “H” used in QED is spelled out in many standard textbooks.

People usually call this “the Schrodinger equation” or “the modern Schrodinger

equation,” but it’s radically different from the original Schrodinger equation

you read about in introductions to quantum mechanics. (This has caused endless

confusion in biology and other areas.)

is the “wave function

of the universe,” the dot represents the change with respect to time, “i” is sqrt(-1), and H is a

strange object called “the normal form Hamiltonian.” (My apologies to the

novice.) Different choices for H correspond to different theories of physics.

For example, the “H” used in QED is spelled out in many standard textbooks.

People usually call this “the Schrodinger equation” or “the modern Schrodinger

equation,” but it’s radically different from the original Schrodinger equation

you read about in introductions to quantum mechanics. (This has caused endless

confusion in biology and other areas.)

One of the most important challenges to physics today is to prove that this dynamical system is a meaningful, well-defined mathematical system, when we use the “H” used in QED.

Why is this so important, and how might it be done?

Mainly it is important because it is a good starting point for proving that many alternative theories are also well-defined. The present fixation on things like superstring theory is basically due to our present inability to work with or understand more than a very small set of possible theories. We basically already know that QED is well-defined, because of very elaborate work in an area called “renormalization group theory (RGT).” But RGT simply won’t work on many possible theories. In order to return to the true scientific method, we need to develop the mathematical foundations which allow us to consider the widest possible range of theories. In addition, proving this for QED is likely to lead to new insights which can be of value in the practical task of trying to make QED predictions more accurately in real-world applications like electronics.

How might it be done? The key idea is to apply the same rigorous mathematical approach which has previously been used in the study of classical dynamical systems; for example see, the classic monograph by Walter Strauss of Brown University, a leader in that branch of mathematics. The initial goal would be simply to prove that solutions to the modern Schrodinger equation really do exist, and are unique, starting from an initial time t and moving forward in time, so long as the initial state has finite energy and is smooth.

This does require developing some new mathematics. The existing theorems about existence and uniqueness are either narrow special-purpose theorems, or require some very restrictive assumptions that would not apply to QED. Above all, the general theorems described by Strauss require that the interaction terms in the dynamics are all repulsive. Of course, to describe even a simple object like a hydrogen atom, we need to survive with the case where electrons and protons attract each other.

It is good to begin by asking: how could it be that a sensible looking field theory could fail to be well-defined anyway? How is it possible if the theory conserves energy, if total energy is always positive, and if the starting state has finite energy? Why has the repulsion term seemed necessary? What is the problem here?

Mainly, the problem is that too much attraction can cause energy to be “sucked up” into a point of attraction, like a black hole but faster. But to prevent that, we can get away with much weaker assumptions in the proof of existence. For example, we can form general assumptions which reflect the kinds of effects we observe in the simpler true Schrodinger equations (see the old book by Titschmarsh), where the derivative terms in the energy prevent the system from being sucked up into a singularity. For QED, we can see directly how such effects – and “Pauli exchange effects” – prevent the hydrogen atom from being sucked up into a singularity, even when the electron and proton are represented as particles of zero radius. (“point particles.”) Once we express this in mathematics, accounting for the usual need for renormalization and regularization, the proof itself should be mainly an exercise in further translation from what we can see plainly in the picture into the corresponding train of logic. (Again, I am not saying it is trivial, but this approach really ought to work, in competent enough hands with enough time and support.) New existence theorems for QFTs would have to use a more suitable measure of distance, other than the usual L2 norm; for example, an electron plus a photon of energy epsilon must be understood to be close to the same electron without the photon.

2015: Last year, at arxiv, I posted a paper “Extension of Glauber-Sudarshan,” which provides a complete mapping between Maxwell’s Laws (or other classical field theories) and the density operators of modern empirical quantum field theory. This year, I have developed a new “F mapping” which can be applied to electrons; there is reason to conjecture that the key results of the 2014 paper can apply to combinations of electrons, nuclei and electromagnetic field, allowing us in principle to calculate exact spectra for atoms by simulation in three dimensions, without trying to explain what an electron actually is (any more than today’s QED does). But will I have time to do the remaining math and write it up, with so much else going on? Maybe.

And now for the nuclear piece.

2015: People have encouraged

me to postpone talking about new opportunities in the nuclear area, for many

good reasons. This is frustrating, since I can now understand connections I did

not see before (nor did anyone else, except maybe Schwinger). Even to explain what an electron actually is,

completely, one must address what is known in electroweak theory; I had some

ideas for how to do that, given in: P. Werbos, Solitons for

Describing 3-D Physical Reality: The Current Frontier. In Adamatzky

and Chen, eds, Chaos, CNN, Memristors and Beyond, World Scientific,

2012. I now have much better candidates for the true Lagrangian, the “theory of

everything,” with supporting analysis, but again, ...

one step at a time. It is crucial to remember that modeling particles as

“topological solitons” does not require

belief in Schwinger’s ideas about what protons are really made of. As with

time-symmetric physics, we need to fix one issue at a time, given the

real-world politics of physics, and given the need to disentangle the logic.

Even today’s simple models of topological solitons, as given in seminal work by

Erich Weiinberg of Columbia University, need lots of

mathematical work.

Still,

I should say a little about some of the important safer possible applications.

Many of us are still excited by inertial

fusion, the hope of

generating electricity “without water” by sending powerful laser

beams into a small chamber to ignite a hydrogen fuel. I am especially excited

by work of John Perkins of Livermmore, who showed

that we can build fuel pellets which are mainly made of deuterium, which

results in a lot less production of radioactive neutrons than fission or easier

forms of fusion. That could lead to a low-cost form of energy generation in

space, much cheaper than solar power, if we ever learn how to make it work. But

how can one model the energy states of such targets? Being able to do

three-dimensional simulations, based on a soliton model (and the results of my

paper on classical-quantum equivalence in spectra), could be useful here. But

then again, it could also open the door to other forms of creativity in nuclear

design.

July 2008: See Soliton Stability and the Foundations of Physics: A

Challenge to Real Analysis and Numerical Calculation. Click here to see the abstract and a

link to the paper itself (‘pdf”). Hard core new mathematics is one of the two

immediate needs, as well as some new experiments touched on in another paper I

posted at arxiv.

Nuclear physics, dark energy and dark matter are the real cutting edge, the place where the dark cloud of massive unknowns comes closest to what we see in front of us in the laboratory. If you would like to develop really radical new technologies, your best hope lies in probing that unknown. This is also the domain where the highest densities of energy are being produced already in this solar system, despite our present clumsiness and ignorance.

Earlier in this web page, I noted how general relativity has been able to predict and fit all or almost of what we have seen about gravity in physics. We cannot begin to make that same assertion for the nuclear realm. There are people who will defend QCD far more ferociously and unscrupulously than I have ever seen anyone defend general relativity. They will tell you that “QCD has been confirmed endless times, and of course it has predicted everything correctly.” But in reality, it has only managed to fit a relatively meager set of things it has tried to predict, and there are major empirical indications which cast doubt even on the things we do know how to test with QCD. Following the scientific method, we should be giving top priority to exactly those kinds of experiments which cast the most doubt, and would pave the way either to greater certainty or to an improved theory. (One thing is for sure. We know from the existence of dark matter and dark energy that there is something out there beyond the scope of the standard model. How else could we hope to find out what it is, if we do not probe our areas of weakness and doubt first?) But this is not being done.

Even though I had taken a graduate course in nuclear physics at Harvard, I was still quite surprised years ago when I read a then-new book by Makhankov et al (The Skyrme Model) describing the present realities of nuclear physics. (Makhankov was then director of a crucial piece of the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, JINR, Dubna, one of the world’s very top centers.) He explained how QCD was utterly useless for predicting or explaining the wide range of nuclear phenomena they focused on there. These included “low and medium energy” scattering, where “low energy” includes what we would see in an H bomb or a fusion reactor. We are all obliged to start with a prayer to QCD, insallah, and prove that we are among the faithful before our work can be published, but many empirical researchers really wonder if there is any connection at all between the world we actually live in and that mythical paradise.

More concretely, the challenge of predicting and explaining the masses and lifetimes of the hadrons is a central challenge in physics today, as important as the challenge of explaining atomic spectra (colors) was at the start of the twentieth century. Some thought that this was a minor part of physics at the time, but it is what really led to quantum mechanics. But could it be that we are offered a similar revolution in understanding, and will never achieve it, because we are now too jaded to take that kind of empirical challenge seriously enough? Why has the careful empirical work of Palazzi and MacGregor not received the level of deep appreciation, respect and follow-up that it deserves from people trying to formulate general theories of physics?

To the best of my knowledge (see the empirical paper cited above), there appears to be a kind of gross mismatch between what we would normally expect to see from QCD and what MacGregor and Palazzi have found, at Livermore and CERN respectively. (In other words, QCD does fine if you don’t count JINR, Livermore and CERN.) The astonishing thing is that there may actually be a relatively easy fix to the problem. Back in the 1960’s, before we even had QCD, Julian Schwinger proposed an alternate model of what hadrons are made of. Instead of being made of three quarks, he proposed that the proton may be made up of three “dyons,” point particles of fractional electrical and magnetic charge. It would be grossly premature to say that we should replace the QCD dogma with a dyon dogma; however, the scientific method does demand that we try to study and evaluate the predictions and mathematical properties of alternative models, including the dyon model as a logical “second member” of a larger family of models.

Why did the Schwinger model not attract more attention in the first place? In my view, there are two main reasons. First, there is the new theological thinking in physics. Second, there is the very strong magnetic attraction in Schwinger’s model, which makes it impossible to use traditional renormalization group theory to prove that the theory is well-defined.

In sum, there are two major immediate threads of highest priority to any rational strategy for the nuclear area. First is to go ahead and do the experiments described in the paper I linked to above, as well as certain interesting new experiments on baryon number conservation. Second is a two-pronged theoretical effort: (1) to calculate the predictions of the Schwinger model for hadronic masses; and (2) to extend the existence work I propose for QED to the case of QED with dyons added.

When I wrote the previous paper, I was frankly worried that strong coupling constants with point particles would result in an ill-defined theory. But on revisiting the mathematics more closely, I now believe that this is probably not the case. (Of course the study of QED with dyons added is extremely important in testing this, but I would expect that same kinds of assumptions that make the QED case work without perturbation theory would also work here.)

This leads to an interesting possibility, much easier and more immediate and more mainstream than what I had in mind with my recent paper on the Schwinger model. The possibility is that we could simply modify EWT so that it contains all the same radiation fields, but the underlying particles are all elementary dyons or electrons. And then use that as an alternative to the entire standard model of physics.

How could we possibly compute the predicted hadron masses (let alone lifetimes) in such a model? How could be we sure that our initial first-order calculations do not miss infinite terms required by an all-orders calculation?

It is much easier than one might imagine. For a crude, “zero order” prediction, one could simply compare the mass predictions one gets with a “constitutive quark” approach with a “constitutive dyon” approach, ignoring binding energies. Akers, working MacGregor, has essentially done this already, and found that Schwinger’s model can get much closer than QCD. For a better, first-order prediction, one can model a three-dyon system (any baryon) as a bound system of three particles in equilibrium, held together by a D(r-r’) attraction, exactly as one does in traditional atomic physics, using variational methods. The interesting aspect of variational methods is that they yield an upper bound on the energy level, even when there are large coupling constants! If we are careful, we need not fear infinite terms due to higher-order effects.

Being careful is somewhat tricky, of course. To confirm the upper bounds, we may map the trial basis functions and wave functions from the realm of D(r-r’) calculations, where wave functions only treat dyons as particles, to the full Fermi-Bose Fock-Hilbert space. This can be done by mapping the point particle in a trial wave function together with its screened potential field into a wave function in the larger space, by applying the usual “P transformation” to the potential field. Then by using the true normal form H we may establish that we have a rigorous all-orders upper-bound for the energy.

I also promised some speculation about how to unify all this with gravity, in the end. If and when we start to have evidence of dyons or electrons having a radius greater than zero, we will have an empirical basis for re-examining some of the classical soliton models I suggested in section IV of my paper on the Schwinger model, which is currently in press in Russian. (For the moment, it is mostly premature, empirically.) As noted in that paper, it is trivial to “metrify” such models to turn them into unified models of models. It is not even necessary to include a white noise, as I once thought – though there are theories of gravity which would want to explore the possibility of such a term.

Added June 2, 2008: To prove that “QED exists,” that solutions exist and are unique for QED as a dynamical system, there are still some difficulties even if one takes the new approach suggested above. Above all, there is the problem that the voltage becomes infinite near an electron, when we represent the electron as a point of zero size and finite charge. That’s a singularity, even using the right norm and P transforms and such. That then leaves us with two obvious ways to proceed – a conservative approach, and an Einsteinian approach.

In the conservative approach, we simply learn to live with singularities. Einstein’s collaborator, Infeld, wrote a paper years ago suggesting how we need to develop new mathematical theory for classical fields in which tractable singularities may occur. After all, there is a rigorous mathematical theory of “tempered distributions.” Why not create a theory of dynamical systems for them? (For all I know, forms of that may even exist already. Google hunters, who not look and see?) And then extend from the PDE case to the QFT case.

The Einsteinian approach is actually more conservative from a mathematical point of view, but more radical for physics. Why not prove existence first for the class of bosonic “soliton” models illustrated in my paper on the Schwinger model, linked to above? These do not involve any singularities. And then prove that one can match the few basic attributes (mass, charge, spin) of an electron as the limiting case of such models, as the radius goes to zero? In fact, one can begin in the “classical” case, by generalizing theorems like those discussed by Strauss, to handle the limited kinds of “attraction” that hold these solitons together, without leading to singularities or explosions. A key brain-strainer here is to understand that there must be region of negative energy density at the core of these solitons, which goes to a limit of infinite negative energy, in order to compensate for the infinite positive energy in the electrical field, in the limit as the radius goes to zero. In reality, we would expect that the true radius of the electron is finite, along with all the energies; however, until and unless we can actually measure a nonzero radius for the electron, the best we can do is represent QED as a limit of more reasonable, smoother theories. If we can meet the requirements with classical PDE but not with the corresponding normal form QFTs, then a “return to reality” may be the only way left to establish existence; however, for the moment, it does seem possible to take the path of classical PDE to nonsingular bosonic QFT to QED as a limit of the latter.

If I get time, that is what I will do next in my own personal core work. But it is hard to get time, even if one can manipulate it.

Final thoughts, August 10, 2008: The basic mathematics is now much clearer to me – but

depressingly far away from options which are considered even discussable in the

fashions of the day.

“Classical”

field theories of the sort I have been studying recently will give good enough

stability and existence results to qualify as reasonable models of physics. When they are expressed in proper

Hamiltonian form (i.e. in the Lorentz gauge, as in the Fermi Lagrangian used in

quantum electrodynamics), they map into a reasonable Hamiltonian operator H via

the “P” mapping I have written about in the past. (i.e.

do “canonical quantization” by inserting the usual pi and phi field operators, but take the normal form product instead

of the classical product for the operators.)

But

here are the weird things, which I tend to despair of orthodox physics of

accepting.

First,

the time-forwards dynamics implied by the classical fields and the P mapping

(the free space master equations derived in the most recent paper at arXiv.org by myself and Ludmilla) are not really relevant to the statistics we

observe macroscopically in experiments. That is because the conventional notion

of time-forwards causality simply does not work at that level.

Second,

what does work is the quantum

Boltzmann equation. For any pure classical state, {p, j} across all space, we know that Tr(r(p,j)H) equals its energy. Thus the classical Boltzmann

equation is exactly the same as the grand ensemble quantum Boltzmann equation.

If we consider what patterns of correlation, causality, and scattering networks

occur within a periodic space of volume V, and let V go to infinity, we can see

that all the scattering predictions and spectral predictions of quantum field

theory are embedded in the quantum statistical mechanics. Consideration of the eigenfunctions of H is essentially just a calculating

device for characterizing the properties of the quantum Boltzmann equation,

which are exactly equivalent to the classical one here. (Caveat: the usual

invariant measures do happen to be equivalent, as noted in the earlier paper by

Ludmilla and myself. However, the set of density matrices considered allowable in

quantum theory is more than just the set which are reachable as P transforms of

allowable classical probability distributions; see my arXiv

paper on the Q hypothesis. This may or may not have important implications

here, where the Boltzmann density is itself P-reachable; this is a question I

need to look into more.). What is most exciting here is that a purely bosonic

theory with a small h(¶mQa)2 term added may give us what we need for a

completely valid quantum field theory on the one hand, and that a quantum

Boltzmann distribution based on that same Hamiltonian may be exactly equivalent

to the same statistical distribution we expect for the corresponding classical

PDE; thus a full “return to reality” may well be possible, not just at the

level of philosophical possibilities, but at the level of specific well-posed

PDE which fit empirical reality better than today’s “standard model of

physics.” Unfortunately – this is the conclusion which emerges from combining the various threads I have

been exploring, each one of which already stretches the present fabric of

physics because it connects areas that are not often connected in today’s

overspecialized world.

In

summary – the classical field theory serves as the most parsimonious, effective

(and well-defined) foundation for physics, so long as

we eliminate the usual time-forwards baggage in analyzing its implications. To

do such an analysis, we derive the quantum Boltzmann equation. The quantum

Boltzmann equation is then the most fundamental and mathematically valid

formulation of what quantum field theory is. Since the usual “Schrodinger

equation” is essentially just a Wick rotation of the quantum Boltzmann equation,

but Wick rotations do not preserve the property of being mathematically

well-defined (e.g. nice oscillatory modes get mapped in part into explosive

modes, and vice-versa), we have no good reason to expect that it constitutes a

well-defined dynamical system. Maybe it does, maybe it does not. It sometimes

seems to work in a formal sense, but no more than that. This implies that the

usual many-worlds dynamics may or may not be a well-posed system. The only

assurance of a well-defined quantum theory lies in the quantum Boltzmann

equation itself. Fortunately, it is possible to make practical predictions on

that foundation, along the lines of my recent IJTP paper, with a further

example in process at this time.

A

second strand of research – justified more by curiosity and cultural pressures

than anything else – is to use the “P” mapping and new norms and such, in order

to see what can be learned about when such systems as ![]() are valid dynamical systems. But when all of the spectrum and

scattering results are implicit in the Boltzmann equation, it is not clear how

important this really is.

are valid dynamical systems. But when all of the spectrum and

scattering results are implicit in the Boltzmann equation, it is not clear how

important this really is.

![]()